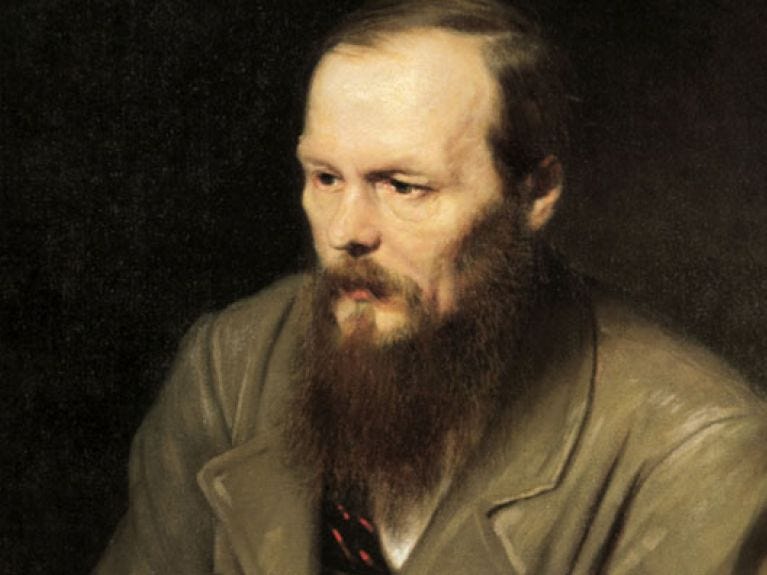

Dostoevsky's Approach to Technology Adoption

How to evaluate new tools without bias. A story about React, GraphQL, Serverless, and Cursor

Hi, it’s Alex Kondov from the newsletter that used to be known as Code Philosophy. You might be wondering why you’re reading this on Substack and not on my blog or via regular email. I’ll be writing a lot more in the next year and I wanted to have a good reading and writing experience for everyone. Starting this week, I’ll be publishing my write-ups here.

When Dostoevsky tells you a story, he doesn’t try to convince you of an idea. Not directly, at least.

Instead, he shows you the opposite - what the world would look like if people believed the opposite of what he does. With each chapter, he pushes it further and further, escalating to the point of grotesque extremes, until the flaws of these ideas become impossible to ignore.

By the end of the book, you accept Dostoevsky's beliefs without realizing what happened.

I've taken a similar approach when I'm exploring new technologies.

I take their selling point for granted without questioning it, and I build something with them. I do things the way the creators want. I follow the advice of the crowd and see how far it takes me.

I take it to an extreme to see where it will start becoming revulsing.

The Engineer’s Skepticism

In my first years as a developer, I was excited by anything.

If someone shared a new library on social media, it was in my dependency list immediately. If there was a new framework, I’d be running production software with it.

New is always better.

But as you expect, I quickly got burned by this behavior, and my early excitement got replaced with natural engineering skepticism.

When I saw a new tool, my first thought was how I couldn’t wait to see how its authors reinvented the wheel this time. I was not only negative, I was cynical.

New wasn’t good. New was dangerous.

I held that mindset for a few years before I saw I was lagging behind. Wait, is Terraform actually a thing? Companies do micro frontends for real?

The evolutionary fear of the unknown was strong, but my fear of becoming a dinosaur in the industry was stronger.

So here are some of the technologies that I Dostoevsky’d myself into loving or hating.

React

When React became popular, I tried it out for a good 10 minutes before I closed the IDE. Components? Passing data to each rectangle on the screen? Unidirectional data flow? That's absurd.

But as I went to conferences and spoke to friends, they all swore by it.

"Try it, just forget about what you've learned so far and build something with it."

So I forced myself.

I disregarded all my knowledge about MVC and the idea that the page should be one cohesive unit. I forced myself to think in components on a low-stakes project and built the whole thing.

I still didn't love it…

But I was surprised at how well this model worked at scale. Normally, there was a correlation between page complexity and how unmaintainable it became. The moment there were a few interactions on the page, bugs started popping up like a game of whac-a-mole.

But with components, I could finally make sense of the data.

The unidirectional data flow felt odd and boilerplatey, but it was predictable. I knew how data traveled, I knew when it changed, and for the first time, I knew when things re-rendered.

I didn't manage to dissuade myself from using React - I started loving it instead. I’ve written two books about it, and it’s still my weapon of choice to this day.

GraphQL

I did the same with GraphQL a few years later when it started gaining popularity in the industry. I was more inclined to try it out because over-fetching was a problem I had personally faced in the past.

So I embraced its philosophy and started building with it.

But this time I had a mixed experience.

Having a single entry point for your data that allows clients to explore it sounds great in theory, but it opens up many problems with permissions and increases the overall complexity of the system.

If GraphQL becomes a standard in your company, it can be an organizational bottleneck. Fitting everything under the same schema can be a challenge, and it takes a while to integrate new data sources.

Federation is possible, but this involves even more complexity and coordination.

At some point, I realized that many teams were using GraphQL just for the sake of using it. They were making specific queries and mutations for every action they needed to take, and clients often consumed all the data the query returned.

They were building REST APIs with an extra network hop on top of them.

So I realized that GraphQL is a great tool that solves two very specific problems - over-fetching and exploration. If you don't have them, stay away from it.

This time Dostoevsky won.

Serverless

Serverless functions came at a time when more people were getting exposed to the cloud, and they had to at least learn to manage their own infra. You had to think about scalability, configuration, runtimes, and whatnot.

It wasn’t like we weren’t doing this before. It’s just that only a few people were focused on it.

Then serverless functions promised that you can just upload your code without thinking about the runtime anymore. Every invocation is done in isolation, and they don't share state.

Want a server but don’t want to manage an EC2 instance? Just deploy each handler as a serverless function.

Then what would normally be a microservice became six separately deployed lambda functions. You couldn't run them in the same environment locally or debug them. While the stateless approach worked well for highly ephemeral databases like DynamoDB, it wasn't such a good fit for others.

Cold starts were a problem, so at the moment I started debating pinging my functions to keep them warm, I realized I had reached my Raskolnikov moment, and the fever had to beat the idea of Serverless out of me.

Lambda functions are great glue between your cloud services and short bursts of compute, but maybe not something to build your entire product on top of.

You only realize this when you take an idea to the extreme; Otherwise, anything may either sound plausible or absurd.

LLM-assisted Coding

I recently channeled my inner Dostoevsky with LLM-assisted coding.

While not a technology that you adopt in your tech stack, it's a pivotal moment in software engineering, and you can imagine how strong my engineering skepticism was at first.

Between the hype and hate for these tools, I got so overwhelmed that I couldn't get a good idea of how and when I should use them.

So, like always, I decided to try and build something and see how far it would take me.

And it worked... to an extent.

Creating something from scratch is times faster. Prototypes become a breeze. Writing down a specific function, extracting logic, or any kind of refactoring in general is much easier.

It saved me a surprising amount of time looking for solutions or algorithms in these moments where I knew what I had to do, but the correct syntax escaped me

But I noticed that if I detached myself from the code too much, I started losing track of the mental model of the codebase. If I let Cursor build freely and just hover over the work, I didn't know where I had to implement changes in the future.

Just ask the LLM to find the place, you'd say. But as the codebase gets larger, I don't know what context to provide it with.

It turned out that it wasn't just my problem.

I do a little bit of startup consulting on the side, and on two separate occasions, founders reached out to me to help them get a product to the finish line because they had prompted themselves in a corner.

Someone had to go into the LLM-generated code and figure out where it was short-circuiting.

I also realized how much of my job is actually not about writing code.

Working in a corporation, I had to figure out how we get data from one team's store to a UI. Sounds simple, right? Then you realize that the data is kept in a data warehouse, and running queries against it is slow and expensive, and there's no other API for that data.

So you have to weigh in the design trade-offs of duplicating the data by consuming the same stream that feeds into the warehouse, and think about storage options. But then, if there's personal data in there, you open your team to auditing, which is a whole different can of worms.

Coding is the easiest part of this whole thing.

I had Cursor open, but I hardly used it. I spent most of my time talking to people and reading.

I used LLMs on every step of the way to research, compare solutions, and look for flaws in my ideas, but people who've worked mostly on greenfield projects don't see that part of the engineering world.

Conclusion

I think this is the only sure way to know if someone is selling you snake oil.

Accept the idea fully, build things the way people are telling you, and remain critical but not skeptical. See how far you can go, and when the technology starts falling apart, take a step back to more conservative choices.

This last bit is very difficult for engineers to do.

Taking a step back in the evolution chain and picking an older tool feels like a concession, a failure even. But I assure you that it's not. Dostoevsky's made a legacy of doing this exact thing.

Very nice. Now a formal thinking structure I will carry forward.