Every Problem is Worth Solving

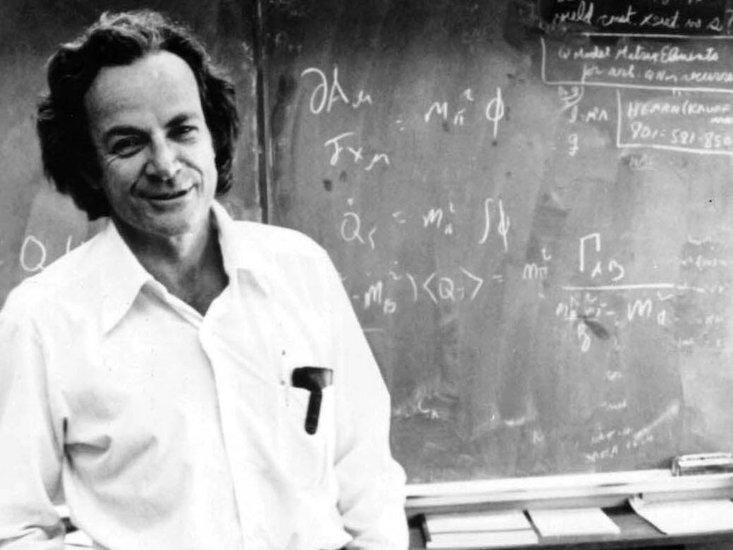

Lessons from Richard Feynman on finding pleasure and success in work

In 1965, Richard Feynman won the Nobel Prize in Physics and got a pile of congratulatory letters. One of them was from his former student Koichi Mano.

While his exact letter wasn’t preserved, we know that among the praise for his teacher, Koichi mentioned that he himself was working on "more humble and down-to-earth type of problems".

You could hear the regret in his voice, the feeling of inadequacy, seeing someone achieve great heights in a field while you're stuck working on things you consider trivial.

Every person cursed with ambition has felt like this at least once in his life. I certainly had.

Someone is changing the world, and I want this person to be me.

I think I read too many books about rocket builders, tycoons, and geniuses in my formative years.

I wanted nothing short of the hardest problems I could work on.

I wanted to learn how to configure CDNs. I wanted to work on the critical services. I wanted to solve performance issues that no one could root out. If there was a challenge, I'd find a way to be on the project so I can get closer to my childhood dream of working on rockets.

This didn't mean just any difficult project, though.

I developed contempt for simple problems. When we needed to build a form, change the colors on a page, or do a small tweak in a legacy project, I avoided these tickets like a cat avoids water.

Migrating data from one storage to another is difficult, but there's hardly any prestige to be found in that. You don't end up in a book for finding a way to move a few terabytes of data.

There's very little work available that we'd call prestigious, both in the academic and the corporate world. Business-as-usual tasks, on the other hand, are plentiful, and someone has to do them to keep the ball rolling. Even AI companies that are developing foundational models need people to clean the training data.

It turns out the real world needs a lot more conditional statements than complex systems.

I developed what you'd call strategic incompetence. I did my best to avoid gaining domain knowledge for our legacy systems and simpler projects. If this makes me seem like a self-centered asshole - I kind of was, yes.

Someone is changing the world, and that person is not me

Then life happened.

We moved to a different city and no longer lived in a commutable distance to a technology hub. I got too tired of startups and the constant hustle. Some unexpected health issues on top of that pushed ambition lower on my priority list.

Suddenly, I started clocking off at 5, and rockets became a distant mirage.

Just like Koichi, I was working on humble problems. I was building UIs, migrating Kafka clusters, and optimizing cloud costs - all things that won't change the world.

I was busy, but I wasn’t satisfied.

I had spent all this time learning about system design, so I could go and never use half of that knowledge. While people are out there building complex products, I'm helping companies make simpler ones.

How do you not feel like Koichi? How do you not get frustrated?

In that moment, I found Richard Feynman's response to Koichi's letter.

Someone is changing the world, and I'm fine if that person is not me

Unfortunately your letter made me unhappy for you seem to be truly sad. It seems that the influence of your teacher has been to give you a false idea of what are worthwhile problems.

In almost all cases, our idea of what's worthwhile comes externally.

The worthwhile problems are the ones you can really solve or help solve, the ones you can really contribute something to. A problem is grand in science if it lies before us unsolved and we see some way for us to make some headway into it. I would advise you to take even simpler, or as you say, humbler, problems until you find some you can really solve easily, no matter how trivial. You will get the pleasure of success, and of helping your fellow man, even if it is only to answer a question in the mind of a colleague less able than you. You must not take away from yourself these pleasures because you have some erroneous idea of what is worthwhile.

This really put the whole idea of solving a problem into perspective.

Is fixing a hole on the street not a problem worth solving? It's a small, insignificant issue in the grand scale of the world, but to the person who steps into the puddle when it rains, it matters.

Picking a more accessible font in the UI is not something you'd get a Nobel prize for, but the people who now have an easier time reading it will be thankful. Optimizing the load time of a back-office app will relieve the frustration in the department using it.

No problem is too small or too trivial if we can really do something about it.

Anything in our power to reduce the entropy in the world and make life better for someone is worth doing.

You say you are a nameless man. You are not to your wife and to your child. You will not long remain so to your immediate colleagues if you can answer their simple questions when they come into your office. You are not nameless to me. Do not remain nameless to yourself – it is too sad a way to be. Know your place in the world and evaluate yourself fairly, not in terms of your naïve ideals of your own youth, nor in terms of what you erroneously imagine your teacher’s ideals are.

Richard Feynman managed to cure that sadness in me with a letter written 60 years ago. Reading that, I was content that the rockets may forever remain out of my reach. I was still doing things that mattered. I was working on worthwhile problems.

Someone somewhere is working on something that will change the world, and I'm fine if that person isn't me.

Good work is worth doing even if it's not worthy of the Nobel prize.

Thank you! , I was in much need of this.

I relate to that so much.