From Today, Programming is Dead

From Paul Valéry's twenty-year silence to painters confronting the camera to programmers facing AI - musings on the craft, commodification, and what survives when technology changes.

I started writing about the intersection of programming and art when I went through burnout. It proved to be the best cure. I’d go down all kinds of rabbit holes, researching artists, finding overlaps between the ideas in software engineering and those in poetry, painting, and philosophy.

They are all an abstraction of a fundamental human quality.

Programming is a wrapper around logic.

Painting is a wrapper around perception.

While I was writing about Henri Bergson’s idea of duration and why that’s important for perceived latency, I came across another Frenchman who admired Bergson but disagreed with him that scientific knowledge couldn’t represent the human spirit.

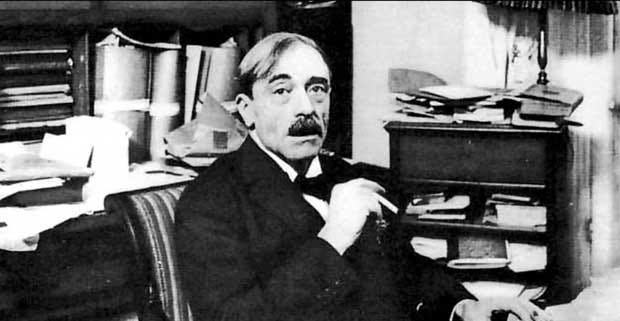

That man was the poet Paul Valéry.

It’s rare to see a writer, a man of the arts, believe that the human condition can be distilled down to numbers. The more I read about Valéry, the more fascinated I was with him.

He showed early brilliance as a poet, but then, at 21, he stopped publishing... for the next 20 years.

“Paul Valéry the great poet who can hardly bring himself to write poetry, who can hardly even bring himself to explain why he cannot bring himself to write poetry”

— Edmund Wilson

He got disillusioned with poetry as a form of divine inspiration and focused on the “exact sciences” - mathematics and physics. He wanted to understand how the mind worked and where creativity came from, not just to produce beautiful artifacts.

Valéry had the heart of an artist and the mind of an engineer.

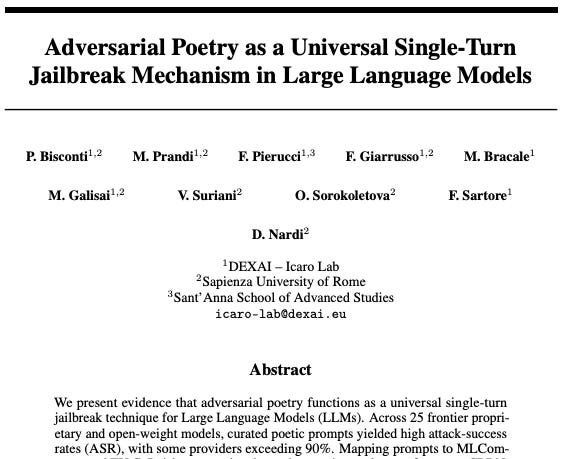

Imagine how he would’ve felt if he had seen this paper published this year.

The authors of the paper have managed to successfully “jailbreak” LLMs with a high success rate through poetry. Maybe the greatest product of the “exact sciences” can fall victim to the power of a wordsmith.

Oh, the irony.

I didn’t manage to do it myself, no matter how hard I tried. However, I’m probably on a list now because of my futile poetic attempts to get an LLM to tell me how to enrich uranium.

Maybe Paul Valéry could get the AI to do it, though.

The Physical Component of Art

In his 40s, he returned to poetry, and by 1928, he’d come full circle with his beliefs. He wasn’t rejecting art for its imprecision again, but pondered how modern technologies were forcing it to evolve.

A lot had changed in those twenty years.

Before that, art mostly existed physically in a single place - a painting was hung in a gallery, a symphony was played in a concert hall. Maybe writing was the only form that we reproduced “massively” at the time.

“Our fine arts were developed, their types and uses were established, in times very different from the present, by men whose power of action upon things was insignificant in comparison with ours. But the amazing growth of our techniques, the adaptability and precision they have attained, the ideas and habits they are creating, make it a certainty that profound changes are impending in the ancient craft of the Beautiful. In all the arts there is a physical component which can no longer be considered or treated as it used to be, which cannot remain unaffected by our modern knowledge and power. For the last twenty years neither matter nor space nor time has been what it was from time immemorial. We must expect great innovations to transform the entire technique of the arts, thereby affecting artistic invention itself and perhaps even bringing about an amazing change in our very notion of art.”

— Paul Valéry

Cinema, photography, and digital media changed art.

These new forms of media proved that the creation can be separated from its original context and copied infinitely. Valéry recognized that this wouldn’t change just how we produce art but what art even is.

I continued reading about Valéry. I picked up a few of his poems, but that quote about how technology changes art was like a splinter in my mind.

I just couldn’t get it out.

As a person whose craft is changing daily because of LLMs, I wanted to learn more about how this has happened in the past. How did painters, for example, react when photography emerged?

This sent me on yet another rabbit hole.

From Today, Painting is Dead!

When the famous artist Paul Delaroche first saw a photograph at the beginning of the 19th century, he said, “From today, painting is dead!”

Around the same time, a magazine published that “the artist cannot compete with the minute accuracy of the daguerreotype” and artists were denouncing photography as the moral enemy of art.

History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes.

The social media posts claiming that software engineering was a dying field quickly came to mind. I remembered all the people encouraging students to focus on other disciplines now that LLMs can write faster and, with time, possibly better than humans.

Posts like these can’t help but send a chill down your spine. As engineers, we’ve been automating other professions for decades now, and we have finally automated ourselves.

But why are there still painters then?

Why are there still artists?

Photography didn’t manage to make painting obsolete - it became a craft of its own. Capturing a moment, knowing how to compose an image, where to put the focus, where to take the picture based on the light - that’s a craft with immense depth.

Photography allowed us to capture moments as they happened - weddings, sunsets, cats sitting in funny places.

It did make something obsolete, though, the aspect of painting focused on recreating reality. The people who wanted a cheaper family portrait would always prefer the photograph.

But this freed artists to explore their imagination and express their subjective view of the world, not the objective one we all experience.

If photography could capture a moment, then a painting could capture feeling, perspectives, and create emotion. That contributed to the explosion of modernist movements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries - impressionism, expressionism, cubism, and abstraction.

Each movement pushed further away from representational accuracy - exactly what photography had made redundant. They explored what paint could express that a camera couldn’t.

The school of hyperrealists is alive and well, though maybe not as popular. There will always be people who value clean, precise, masterful brushstrokes above all else.

The Painters of the 21st Century

I remember seeing the early GPT demos that showed how it can turn the prompt “make a button that looks like a watermelon“ into an actual, well-written React component with a green border and pink background.

We’ve gone a long way since then.

A scarily long way.

We’re the painters of the 19th century, wondering what our craft will look like when it’s all said and done, but no prediction in the last few years has proven to be an absolute truth.

We didn’t lose our jobs, but companies expect engineers to be more efficient. We didn’t turn into software designers who only orchestrate agents, but we read a lot more code than before. English hasn’t become the primary programming language, but knowing how to express requirements has become even more important.

It’s undeniable that the post-LLM world is different, but I believe that many of my colleagues are focusing on the wrong things.

AI allows me to work faster, to be more productive.

I don’t think that’s the point.

Artists didn’t take up cameras so they could make more portraits.

They explored the problems that photography couldn’t solve. That’s where their value was. I’m not excited by the opportunity to spew out trivial software faster. I think I should be working on software engineering problems that LLMs are not that good at.

Code will become an abstraction, just like machine code.

There’s an important difference here that people are omitting. Compilers are deterministic. They have plenty of checks, defined behaviors, and useful error messages when something goes wrong.

LLMs are statistical next token predictors.

They can write code much faster than I do, probably better than I do (if not now, then in a couple of years), but its output depends on the weights of the model, and it’s not idempotent. You can’t treat it like a black box.

We’ll become agent orchestrators and code reviewers.

I still see the human behind the keyboard as the bottleneck in this potential future. Someone’s name has to be on the PR, and someone has to sign off on it.

I’m getting a sharp pain in the head just imagining what it would be like to get woken up at 3 AM because a critical service is failing and an agent made the last merged changes.

So, How Will AI Change Software Engineering?

I really have no idea.

I don’t think I should even try to guess anymore.

I’ve conceded that I will be surfing the technology waves others create, and I’ll always be a step behind. I no longer have the industry insight that people in the Valley have. The small Bulgarian city I live in doesn’t even have an airport, let alone a technology hub.

But I can tell you what I’ve seen so far.

Earlier this year, I was helping out a friend with his startup, and his workflow was straight out of a sci-fi novel. He was actually talking to the LLM. He used Whisper to transcribe what he said, clean up the “uhs“ and “ahs”, and structure his thoughts.

Then he’d submit a multi-paragraph message to Cursor, giving a detailed description of what he wanted it to do as if he were giving instructions to a junior engineer.

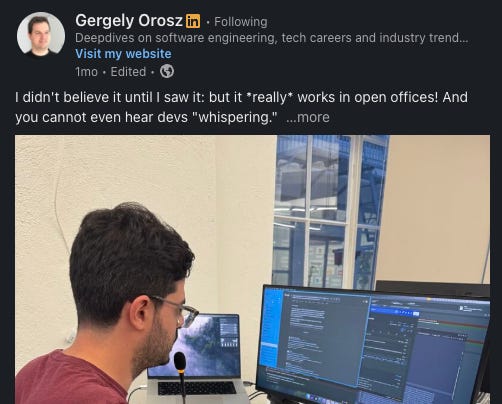

He’s not the only one to do it, either. Gergely Orosz from The Pragmatic Engineer posted about it on LinkedIn, and it seems like a popular practice that I’m trying to adopt too.

Who thought the most efficient way to build software would be with our voices? Show me the influencer who predicted we’d be casting spells this way.

Speech is a faster medium than writing, so you can iterate faster, and you don’t even need to be that precise - you can put your transcription through an LLM first to structure it.

Tolerance, Non-Determinism, and the IDE

Based on how self-contained the problems they’re solving are, some software engineering fields are more susceptible to disruption than others. In a report from earlier this year, Anthropic said that one of the most common use cases for Claude was building user interfaces.

If the entire problem can be represented as code in the IDE, then LLMs can be trained more efficiently on it.

Front-end development brings markup, styles, and logic together in one place that is easy to reason about. Of course, there’s the aesthetic element where algorithmic knowledge alone is not enough. It requires intuition and taste that are only built by spending time outside of the IDE.

In his latest interview with Gergely Orosz, Martin Fowler says that we will have to start thinking in terms of tolerances like other engineering fields do. What are the tolerances of non-determinism that we can handle?

Again, in front-end development, non-determinism is less of a problem. Imprecision with pixel alignment can cause frustration, but it won’t affect the correctness of the final result. It’s a field with better tolerance for error.

In data engineering, on the other hand, inconsistent behavior is unacceptable because it risks corrupting data or producing a misleading result.

This shouldn’t be taken to mean that front-end development is a dying craft.

A quick glance at all the shovelware pushed out onto the internet will show you just how important taste and imagination are.

The only conclusion we can make so far is that the valuable aspects of software engineering are the high-stakes problems whose solutions can’t entirely fit into the IDE.

Whatever that means.

The Library of Babel

We underestimate how many of the problems we’re working on have already been solved.

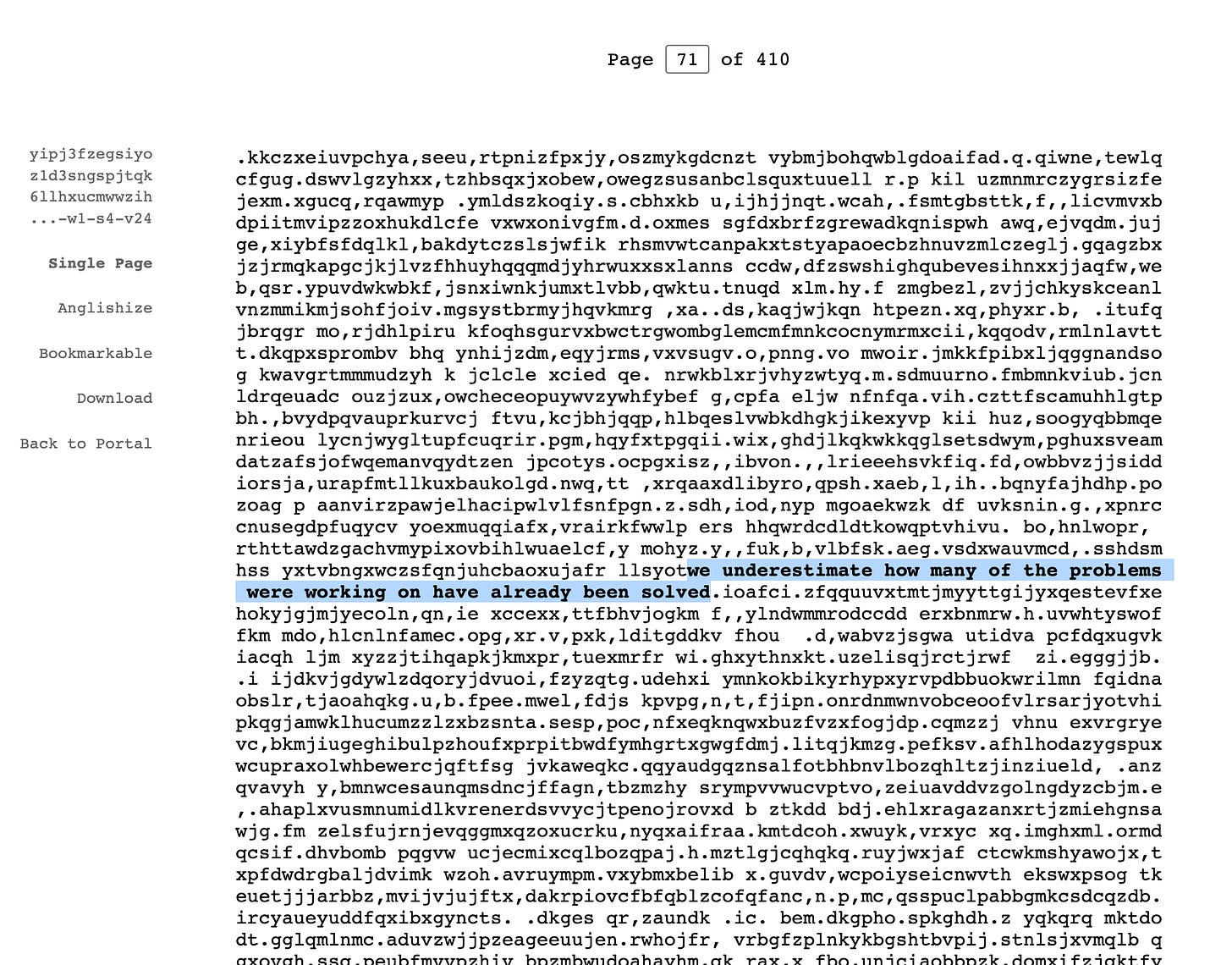

We say that LLMs are just stochastic parrots, but I like to think of them as a portable Library of Babel. This is a project created by Jonathan Basalt that brings Jorge Luis Borges’s famous 1941 short story to life as an actual, searchable online library.

In Borges’ story, the Library of Babel is an infinite library containing every possible 410-page book that could ever be written using a specific character set. The digital project does something similar - it algorithmically generates every possible page of text (3,200 characters long) using a limited alphabet.

The library theoretically contains every possible combination of letters, spaces, commas, and periods that could fill a page. This means it contains every book ever written, every book that will be written, every coherent sentence.

While it technically contains all knowledge, it’s essentially useless for finding information because the vast majority is random gibberish, and finding anything meaningful is nearly impossible without already knowing exactly what you’re looking for.

Just like an LLM.

My Plan for the Future

Paul Valéry must be happy that art and science turned out to be two sides of the same coin.

I wonder if he would’ve spent these 20 years on poetry then? Whether he would’ve given up entirely? Maybe actually published more?

These kinds of write-ups usually end with a piece of advice, a look into the future, a strong statement about what it would look like, or an opinion, at least.

But I can only tell you what I plan to do.

I won’t build passable UIs, I’ll build great ones. I’ll think about every pixel, every text, every color. I won’t build systems that are good enough. I’ll think about trade-offs, access patterns, and scale. I won’t treat code like a black box yet - it’s not ready to be treated like one. I’ll read through every line, every function, and every variable.

I won’t settle for mediocrity.

I’ll look for answers in the Library of Babel.

I’ll build things that make people’s lives better, with or without AI.

And if there comes a time when my services are no longer needed, and software engineering remains an artifact of the past, then I’ll happily install drywall knowing I’ve done good work.