The Quality Without a Name

How the architect Christopher Alexander inspired the software engineering field to create design patterns

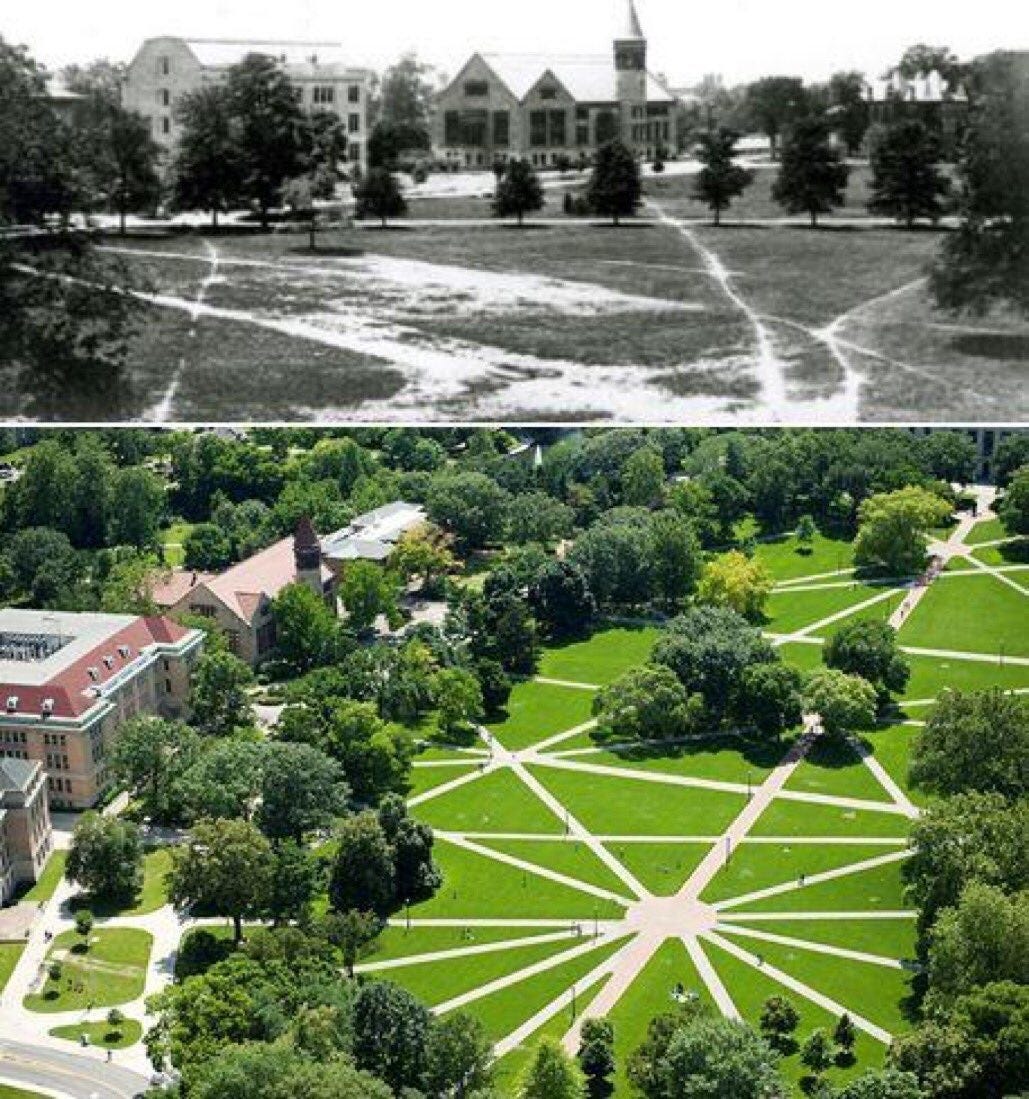

In the early 1970s, the University of Oregon hired Christopher Alexander to expand and redesign their campus after a wave of protests from the students and faculty members.

The campus apparently had many problems, but the fact that it had log trucks driving through it should be enough proof that it needed to change.

It sounds like a task that any architect would be more than eager to take up and flex their knowledge of aesthetics. It’s not every day that you get the chance to leave your fingerprint on a place that’s home to thousands of people. And a place full of brutalist buildings isn’t a high bar - anything would’ve been an improvement.

But Alexander didn’t come out with a grand design.

He didn’t plan it all up front by himself.

He let the campus design itself naturally.

They observed foot traffic to see how students move from one class to another. They let people create desire paths in the lawns to see where they should pave the path. They interviewed students, faculty, and staff members to find out how they can make that space more comfortable for them.

Christopher Alexander was just the person who gave the campus a voice.

Habitability

He believed that form follows function, and if you understand perfectly how something needs to work, you will have no problems designing it. Design for the sake of it is meaningless. It’s liveable and habitable spaces that give people satisfaction and fulfilment.

When I walk into an office building, I feel unease, like I should sit with my back straight. I spend the first ten minutes trying to get the chair to the proper height, I wait in line at the coffee machine, and I try to find an angle where the sun isn’t blasting straight into my monitor.

It just doesn’t feel right.

The office is not a home, you’d say. But not every home is a home either.

You must’ve seen these overly designed apartments where if you move a piece of furniture slightly to the left, the whole place just feels off. That’s because it wasn’t designed to be habitable - it was designed to follow someone’s standards of beauty.

The Quality Without a Name

Alexander believed that there was a specific quality that some buildings have that makes them livable, but we couldn’t exactly pinpoint what it was. It was hard to give it a name, but we knew when it wasn’t present.

It made places feel right to live in. It made them fit their purpose. And even though it was impossible to name this quality, it wasn’t subjective because people’s opinions tend to converge when they’re looking at the same thing.

It wasn’t just based on vibes, but it was a quality without a name.

So Christopher Alexander set out to create what he called a pattern language - a collection of all the different ideas that you can find in places that have this quality. We’ve been making buildings for so long that we can recognize the common ideas between the good ones.

When they have a choice, people will always gravitate to those rooms which have light on two sides, and leave the rooms which are lit only from one side unused and empty. Locate each room so that it has outdoor space outside it on at least two sides, and then place windows in these outdoor walls so that natural light falls into every room from more than one direction.

Each pattern represents a problem in our environment and a fundamental principle that you can follow to solve it. He doesn’t give a prescriptive approach, but an idea. How you apply that idea is up to you and the environment in which you’re working.

This does not mean that all ways of making buildings are identical. It means that at the core of all successful acts of building and at the core of all successful processes of growth, even though there are a million different versions of these acts and processes, there is one fundamental invariant feature, which is responsible for their success. Although this way has taken on a thousand different forms at different times, in different places, still, there is an unavoidable, invariant core to all of them.

Small diversion, but this idea reminded me of a quote from Anna Karenina:

All happy families are alike. All unhappy families are unhappy in their own way.

The principles are always the same, but at the same time, their application isn’t identical. Alexander’s ideas weren’t about measuring inches and applying hard rules - if you use these patterns a million times, you’d get a million different results.

The Timeless Way of Building

I learned about Christopher Alexander’s works from a book called Patterns of Software, published in 1997. I don’t even remember why I picked it up, but it helped me realize how much our young industry steps on the knowledge of previous builders.

After that, I started reading his book The Timeless Way of Building as a way to get a first-hand impression of his writing.

In all honesty, at first it felt like the ramblings of someone who’s spent far too long in an industry and has lost himself in its artistic margins. It happens often to intelligent people. Newton, for example, spent the better part of his life researching alchemy, and at first, I thought that this pattern language was just Alexander’s alchemy.

But the more I read, the more things started making sense.

He had written a philosophy book with architectural examples.

You know how when someone is saying something you deeply agree with, you nod and smile like you’re having a seizure? That was me when I was reading it.

But it wasn’t just me.

The widely popular Gang of Four Design Patterns book that you’ve been asked about during interviews was largely inspired by Alexander’s work.

Programming Design Patterns

We’ve written enough software now to see that good software looks the same. This quality without a name is present in our field, and even though we can’t put our finger on what exactly it is, design patterns bring us closer to it.

Just like Christopher Alexander’s pattern language, they are the repeating successful solutions to the problems we face.

The way we’ve taken this idea wrong is that we’ve tried to formalize it too much. I’ve had interviews where I’ve been asked to implement the Strategy design pattern like I was reciting a poem in middle school.

Alexander was against this.

But as things are, we have so far beset ourselves with rules, and concepts, and ideas of what must be done to make a building or a torn alive, that we have become atraid of what will happen naturally, and convinced that we must work within a “system” and with “methods” since without them our surroundings will come tumbling down in chaos.

These patterns were never meant to become hard rules. They’re abstract ideas. In his example, Alexander doesn’t tell you the size of the windows or their exact positioning, or the layout of the room. He just tells you where people tend to stay and how to achieve this.

Code lives and changes. Too much structure makes it look like a statue - you can marvel at it from the side without touching.

A million applications, a million different results

Christopher Alexander says that we can identify these patterns in architecture because we’ve been building structures for a long time. It takes time, trial, and error for them to surface.

Now we finally have the catalogue of building software at scale that will allow them to surface in our industry.

But if you try to be too specific about the patterns and apply them like an exact science, your codebase turns into one of those overly-designed apartments I mentioned in the beginning. It can’t stand change.

I’ve seen astonishing abstractions that would just crumble like a house of cards the moment the business makes even a minor change.

Yet, people are reluctant to accept that there are fundamental principles that make software good. I was once even called a snake oil salesman for daring to suggest this. Everyone thinks their problems are the hardest to solve, that their domain is so specific and different that no engineer has faced them before.

The truth is that it most likely isn’t.

Desire Paths in Software Design

Alexander’s idea to design the University of Oregon’s campus can be translated to software design quite well.

Watch the desire paths.

See which files people change regularly. Don’t try to abstract everything from the start. Tolerate some repetition to let patterns emerge.

The same way he spoke to students and teachers, you can talk to your product managers and stakeholders. Understand the problems they have well enough, and the application will design itself.

We’re constantly changing the places we live in. A well-designed space can be organized in many different ways within its boundaries. In the same way, we need to create boundaries in software where we can add functionality and contain complexity.

A well-designed module gives you the freedom to implement it as you like, and fits into the rest of the application like a puzzle piece through its interface.

When I look back at the last decade of working as an engineer, I can see the overlap between the companies that build good products. I’m not measuring success by how many enterprise integration patterns they apply, but how productively they make changes and ship them.

This is what makes an application living and makes it a joy to work with.

We Don’t Talk About the Quality Without a Name

Correctness is easier to discuss, and it’s easier to prove. It’s difficult to prove that you’ve implemented Alexander’s quality without a name. Correctness gives a sense of accomplishment, while design gets you out of the comfort zone where compilation without errors means success.

Programming design patterns were an attempt to turn design into science, to give the quality without a name an actual name, but they fall short.

We have been taught that there is no objective difference between good buildings and bad, good towns and bad.

The fact is that the difference between a good building and a bad building, between a good town and a bad town, is an objective matter. It is the difference between health and sickness, wholeness and divided-ness, self-maintenance and self-destruction. In a world which is healthy, whole, alive, and self-maintaining, people themselves can be alive and self-creating. In a world which is unwhole and self-destroying, people cannot be alive: they will inevitably themselves be self-destroying, and miserable.

But it is easy to understand why people believe so firmly that there is no single, solid basis for the difference between good building and bad.

It happens because the single central quality which makes the difference cannot be named.

Many engineers will tell you that the Strategy design pattern has no room in React development, for example, because they’ve only been exposed to a specific implementation and not the principle behind it. But the idea is applicable everywhere, regardless of language.

It just doesn’t have a name.

Thank you, it was interesting