We Don't Live in Mathematical Time

How Henri Bergson's philosophy of duration explains why your users complain about latency

In this issue of Fragments of Code, we explore how latency is not just a number and how the physics of distributed systems shapes user experience. We draw on Henri Bergson’s philosophy of duration to understand why building humane software means accepting that time is subjective and emotional. By Alex Kondov.

Henri Bergson believed that time eluded mathematics and science. While they attempt to measure an immobile, complete line, what we experience is a mobile and incomplete one.

For the scientist, time moves with the same speed, while for the individual, it’s never constant - it speeds up, slows down, and even goes back.

Bergson called this lived, quantitative time duration - the continuous flow of experience as it is felt from within, not measured from the outside. It’s the time we live, not the time we count. His idea sits at the crossroads of metaphysics, psychology, art, and I believe that it has touchpoints with software engineering as well.

As a front-end developer, I’m the first person to learn when someone experienced duration in a negative way.

“The dashboard is slow”

From a mathematical perspective, 500 ms is not a long period of time, but the way the person behind the keyboard experiences it is different. We can’t stare at a blank loading page anymore. Loading spinners are not good enough, waterfalls are an anti-pattern, and skeleton loaders are only good in moderation.

Because time is subjective, elastic, and emotional.

“Time is invention and nothing else.” — Henri Bergson

I’ve lost count of the number of JIRA tickets I’ve received throughout the years because someone felt like there was something wrong with a page. Since duration is felt in the interface, the front-end is where this discomfort bubbles, even when the cause is somewhere deep in the underlying system.

Duration distills down to latency, the time our application spends waiting. Latency is where clock-time collides with lived-time.

For Bergson, duration is intimately connected to consciousness - our inner life is a continuous flow where past and present come together.

When you meet an old friend, you don’t see them as they are now - your history together and your memories shape the current moment. A song is not a collection of notes that you take one at a time - the earlier ones persist in your mind and shape the music.

“The pure present is an ungraspable advance of the past devouring the future. In truth, all sensation is already memory.” — Henri Bergson

This stands in stark contrast to how science typically treats time, but Bergson wasn’t anti-science. He believed that this approach, while useful for practical and scientific purposes, fundamentally misrepresents the nature of lived reality.

The Speed of Light Problem

Henri Bergson developed this idea to address the objections of free will, but we’ll only be dealing with the humble problem of moving network packets, because that’s how our work as engineers shapes how people experience duration.

The time between the browser sending a request and it receiving the response is the end-to-end latency, the round-trip time. Some of that time, the server spends actually working with the data, massaging it, putting it in the right shape to be displayed.

But this data doesn’t appear in our React application’s memory out of nowhere.

It has to physically travel to us, go through a maze of network hops, and then appear on the screen. Behind the UI of every complex software, there’s a distributed system. Microservices call other microservices, databases live in different regions, and third-party APIs are scattered across the internet.

We can optimize our code’s performance, but we can’t optimize the laws of physics.

The maximum speed that energy and matter can travel is the speed of light. In a fiber cable, though, they move a little bit slower. It’s still astonishingly fast, and an absolute engineering miracle that it can happen at all, but it means that there’s an overhead that we pay every time we’re transferring data.

The round-trip time for a request from New York to London and back is ~50ms. The same request will take ~160ms if it has to travel to Sydney and back.

In other words, distance is a factor.

Perceived Latency

We do not live in mathematical time. We live in duration.

A 200ms delay when I click the “Publish” button on this article will be something my brain doesn’t register. But if I feel even a sliver of delay when I’m playing Counter-Strike, rushing bomb-site B, I’ll have a breakdown.

Users perceive latency differently depending on what software they’re using and how it handles delay because they experience Bergson’s duration.

We started adding loading spinners in the UI to give people something beautiful to look at and create the impression that the software is hard at work on their request (while in reality, we’re waiting for data to flow down the fiber optic cable).

But as interfaces became richer, the spinners grew in number, and they started creating those waterfall effects where just as one disappears, it triggers the next data fetching operation, and the user feels like they’re unpacking a Russian doll of spinning SVGs.

At a large scale, this wasn’t a good solution, and it did more harm than good in how people experience duration.

That’s why we started using skeleton loading screens that mimic the structure of the page and don’t cause a layout shift. That’s why LLMs stream their progress so it feels like a natural conversation. Try using an AI agent that doesn’t do that and see whether your perception of time changes.

Bergson argued that lived time is continuous, but in our field, latency fragments it. It takes the person behind the screen out of their flow.

A person doesn’t count the milliseconds, but they will bounce off an e-commerce website because of that delay.

When the system visually responds immediately, even if it finishes later, the continuity of user intention remains intact.

That’s why we use optimistic updates for operations that are likely to succeed. When you double-tap a post on Instagram, it will take a while for it to get recorded and propagated to all your followers.

But the person sees the heart icon turn red instantly. Consider how differently they’ll experience duration if they have to wait for a loading spinner every time they like something.

Not All Network Hops Are Equal

A request spends a certain fraction of its time traveling across the globe. So the more requests you make, the more time you’ll spend waiting for them to move from one part of the world to another.

I learned about distributed systems from the perspective of a front-end developer who is greatly concerned with a page’s initial load time.

The idea that we will have more services that will pay the latency cost when they communicate with one another didn’t give me peace. Even if we get every ounce of performance out of them, we can’t cheat physics.

So many services, so many databases, so many requests, so much latency.

There are horror stories about websites not loading when the data they fetch gets lost in this maze. This is no longer a question of Bergson’s subjective duration and human experience. A website not loading is a purely objective metric.

This is when I learned that not all network hops are created equal.

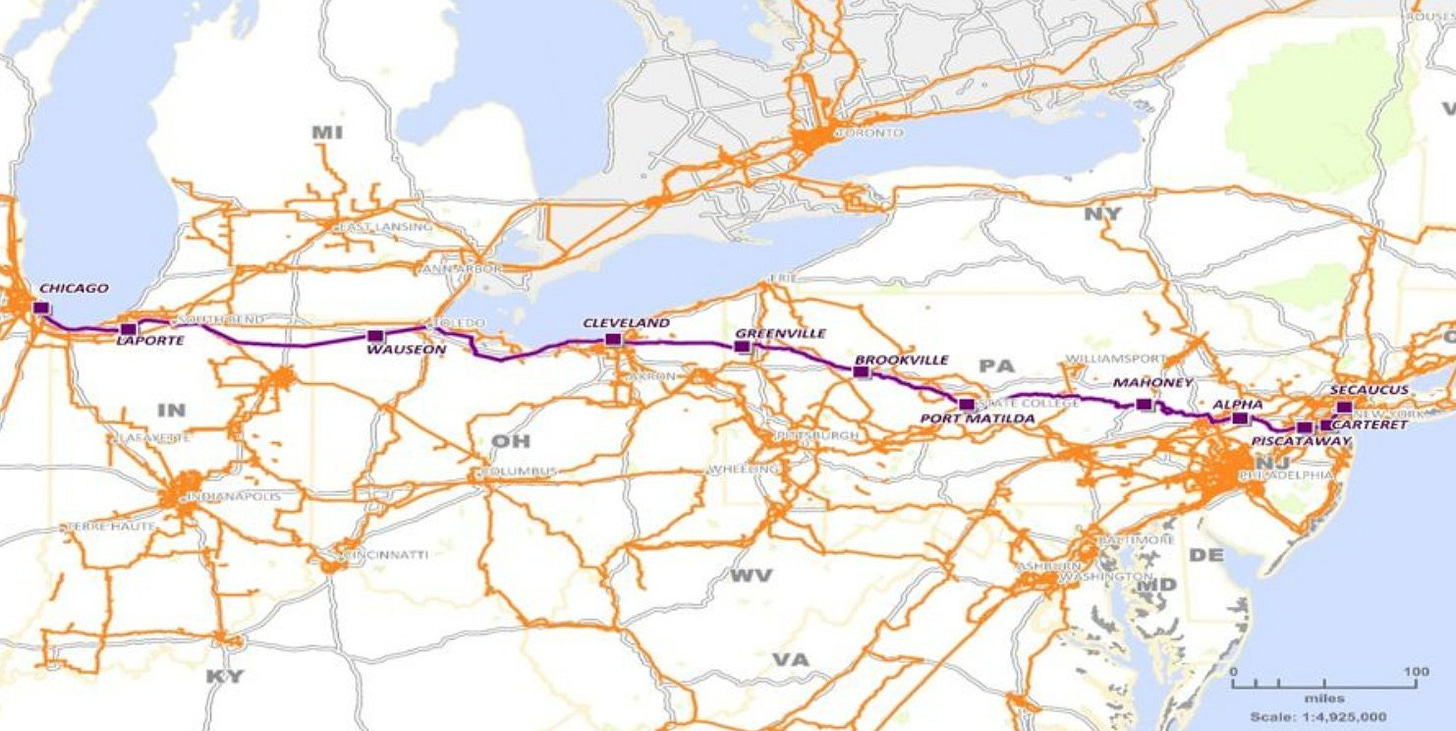

When a browser makes a request to a server on another continent, that request travels through the public internet. It bounces between ISPs, goes through submarine cables, and passes through multiple routing hops that add latency.

But when your services are talking to each other inside the same network, like a Kubernetes cluster, things are different.

They are often running on machines in the same data center, sometimes on the same physical rack. The network distance is not thousands of miles - it’s meters. Instead of the public internet, these requests travel through a dedicated private network. There are fewer hops, less congestion, and the network infrastructure is optimized for exactly this kind of internal communication.

The latency between such services becomes insignificant. That’s why we can build complex distributed systems spanning hundreds of microservices.

Percentiles and Experience

Because of that subjective duration, measuring latency in a meaningful way is difficult. We need to do it in a way that gives us insights into people’s experiences, so we need proper metrics and some empathy to understand it.

Averages don’t work here.

If your request takes 1000ms but mine takes 100ms, on average, we’ve both waited 500ms. But this doesn’t reflect reality.

Neither of us has actually had such an experience - we’ve had one fast and one slow execution, but the average will hide that reality.

Percentiles can get us closer to the experience of duration.

They tell us how many of the requests we handle fall below a certain number. If our P99 latency is 100ms, for example, this means that 99% of our requests are handled for 100ms or less.

By using different percentiles, we can paint a more complete picture of our product’s behavior. This is difficult because we’re attempting to understand what a large group of people is experiencing, and making conclusions for the whole is always more difficult than for an individual.

Measuring P50, P90, and P99 can help us paint that picture.

In his talk “How NOT to Measure Latency“, Gil Tene explains how we need to know our maximum latency because, on a grand enough scale, the maximum latency still affects a large number of people.

We build distributed systems because of scale, and 1% of 1 million is still 10,000.

Also, we rarely retrieve all the data we need with a single request. We make multiple requests to different services and systems, both internal and external, to assemble the data for the page.

The chance of us experiencing the maximum latency for a percentile is actually a lot higher than it seems.

Noise and Signal

But why not P100? Why don’t we measure everything? Why are we leaving 1% out?

That last 1% of requests is usually dominated by events we can’t really affect - cold starts, garbage collection pauses, packet loss, and VM restarts. We’ll get values that fluctuate so dramatically that they’ll confuse us more than give us insights.

Our goal is to get closer to understanding how users experience duration, and this will introduce so much noise that it will make it harder, not easier, to do so.

Your P100 latency will be dominated by mobile users walking into elevators.

Still, we can be more thorough with our measurements. We needn’t monitor only the end-to-end latency. In a large system with many services, measuring the latency of each service’s individual endpoints is a fine approach.

A spike in the latency is usually a signal that something is wrong - queries are slowing down, requests are being throttled, somewhere something is degrading.

Moving the Mountain

“If the mountain won’t come to Muhammad, then Muhammad must go to the mountain.“ — Francis Bacon, retelling Turkish folklore

Some companies try to make the mountain come to them, and some of them even succeed.

Dan Spivey developed a trading strategy where he sought out tiny discrepancies between futures contracts in Chicago and their underlying equities in New York. However, he wasn’t able to execute it because he didn’t manage to get the market’s lowest latency line.

So his company, Spread Networks, built a $300 million cable from New York to Chicago that improved the latency from 13.1 milliseconds to 12.98 milliseconds.

Now, I’m no quant. I can’t fathom how crucial less than a millisecond is, but I want to highlight the lengths people are ready to go to reduce latency, and how hard it is to do so. Dan Spivey managed to move the mountain at least a little.

Now, most companies are not Spread Networks. They can’t move the mountain to them. They have to go to the mountain.

This is where edge computing comes into the picture. By moving storage and application code closer to the user, we reduce latency and response time. But instead of managing one central server, we now need to manage multiple and deal with complex challenges like data replication.

Latency lives in the graph, but every complex system should be built to serve humans and make their lives better. By designing our systems and interfaces for duration, we build more humane products.

Bergson would be proud.